The 54th annual super bowl was a nail-biting game and included performances that got you…

Miami’s film industry is on life support. Can it survive?

Ben Kanegson remembers the good old days of the Miami film industry — and by good old days he means 2015, when production on the second seasons of the HBO sports-comedy series “Ballers” and the dark Netflix drama “Bloodline” overlapped and he was forced to choose between them.

Kanegson, a veteran camera and crane operator who also runs his own equipment rental company, went with “Bloodline.” He’s currently working on the third and final season of the show, which will wrap production in the Florida Keys in March.

“One of the things thats keeping me in Miami is I have seven more weeks of solid work here, working on the last show that’s filming in the state,” he says. “But this is the end of the line. The No. 1 topic of conversation among the crew as we go back and forth to the set every day is ‘Where are you moving to?’”

“A lot of them have already relocated to Georgia and have advanced their careers. When there’s demand for the work that you do, there’s room to move up in your field.”

But in Miami, as in the rest of Florida, the film and television industry is on life support, unable to compete with other states with generous tax incentives that help studios defray the ballooning budgets of filmed entertainment. At risk in Miami-Dade alone are the 4,900 jobs, $249 million in personal income and $20 million in tax revenues created over the past five years, according to the county’s Regulatory and Economic Resources Department.

Without state tax incentives, however, the film and TV industry is flat-lining. “Ballers” left South Florida after two seasons, lured to Los Angeles by an aggressive tax incentive aimed specifically at relocating TV series that had previously filmed elsewhere. “Bloodline” will end after its shortened 10-episode third season, even though the show’s creators are rumored to have planned enough story for five.

High-profile Hollywood studio movies such as the upcoming Dwayne Johnson-Zac Efron “Baywatch” and the Owen Wilson-Ed Helms comedy “Bastards” spent only a few days filming in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties. That’s a dramatic change from 20 years ago, when an average of 15 feature-length films were shot here from start to finish each year between 1994-1996.

That number went down in the early 2000s, when Canada lured Hollywood away from the U.S. with incentives and a favorable currency exchange rate. Since then, most states have drawn productions back, but Florida is no longer able to compete. Recent and upcoming movies that are set in Florida, such as Ben Affleck’s “Live By Night” and the Chris Pine-Octavia Spencer drama “Gifted,” were shot in Georgia. According to Gus Corbella, the chairman of the Florida Film and Entertainment Advisory Council, the state has lost out on $650 million in film and TV expenditures since 2013.

Even “Moonlight,” the Oscar-nominated drama about the coming-of-age of a young man growing up in Liberty City, was almost shot outside of Miami.

“I had to face my producers and say, ‘Look, I know we could maybe set this movie in New Orleans or Atlanta, because those states have tax incentives, and the budget would go a lot further,’ ” says “Moonlight” writer-director Barry Jenkins. “For a movie of this size [$5 million], that would have made a meaningful difference. But we stuck to our guns and took the hit and decided to make it in Miami. I’m glad we did, because that was the only place to make it. But if we’d had those tax incentives, the movie could be even a little bit stronger aesthetically than it is.”

Financial squeeze

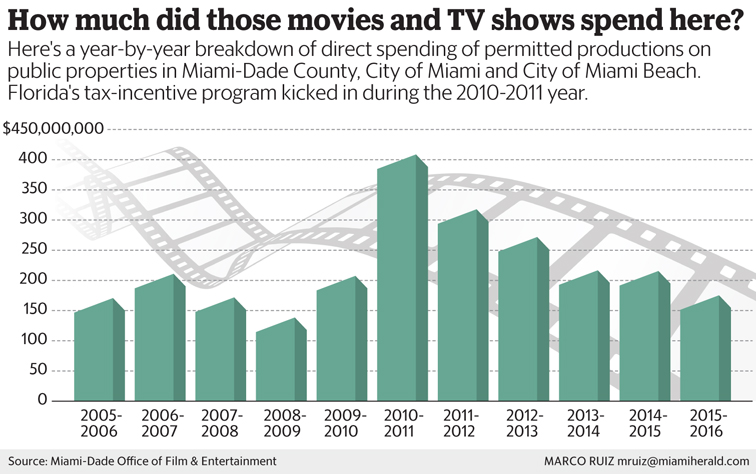

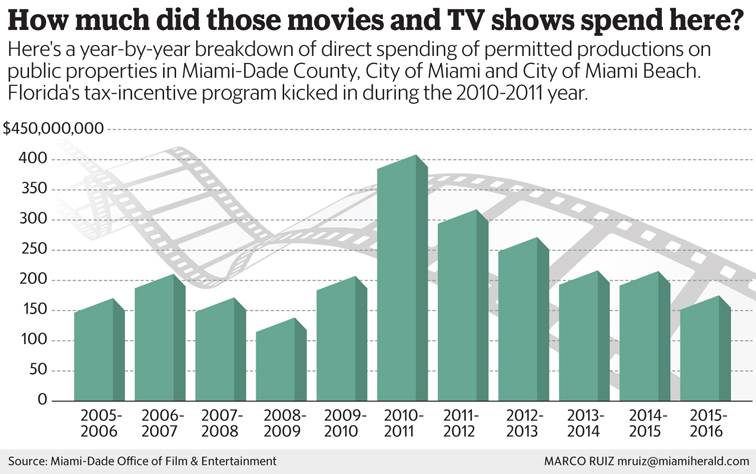

According to the Miami-Dade Office of Film & TV Entertainment, permitted movie and television productions spent $410 million in 2010-11 on public properties in Miami-Dade County, the city of Miami and the city of Miami Beach, accounting for 70-80 percent of total expenditures. In 2015-16, that number dropped almost 60 percent, to $175 million. The figure is expected to continue to plummet.

Year-round production of scripted series at Telemundo Studios and TV shows at Viacom International, which currently occupies an 88,000-square-foot studio facility in downtown Miami, aren’t big enough to sustain an industry that relies on larger productions to maintain a steady infrastructure.

EVERYBODY I KNOW THAT’S TRIED AND TRUE AND ARE REAL ARTISTS IN THE INDUSTRY HAVE RELOCATED. WE’VE LOST SUCH A DEAR INDUSTRY HERE.

“Moonlight” production manager Jennifer Radzikowski

The dearth of work has reached a critical point. Locals who make a living as electricians, carpenters, decorators, technicians, location scouts and other below-the-line jobs — anyone who is not an actor, writer, producer or director working on a movie or TV show — are being forced either to move out of state or change careers altogether, because family obligations keep them here.

The Florida Entertainment Incentive Program, which was launched in 2010, established a pool of $296 million in tax credits for film, TV and video productions that required 60% of the cast and crew of any eligible project to be based in Florida. The program was supposed to last five years, but there were so many takers that the money ran out in three.

Since then, Florida legislators have repeatedly voted not to replenish the funds. The program officially ended on June 30, leaving the state unable to compete with Georgia, Louisiana, California and other states that offer as much as 30% in tax credits.

Florida isn’t the only state to turn away from tax incentives. Texas and Michigan have also recently cut back or ended the rebates altogether, because it’s difficult to prove a direct return on investment.

Tourism and economic benefits are undeniable. For example, a 2015 study by the Monroe County Tourist Development Council on the economic impact of the first season of “Bloodline” revealed a combined film production and tourist spending of $95.4 million, the creation of 1,738 jobs and an economic output of $158.7 million.

There are also casual, unpredictable benefits. Edna Cadigal, the manager of Jimmy’s Eastside Diner in Miami, the restaurant where the climactic sequence of “Moonlight” takes place, says business has increased by 5 percent since the release of the movie in October — mostly from locals who want to sit in the same booth where the actors sat and take photos there.

$650 million

$650 million

Florida’s estimated loss on film and TV work over the last three years

But despite the perks, government isn’t budging. According to a study by Film Florida , a non-profit association that represents Florida’s entertainment industry, the state has lost out on more than $650 million in projects, 110,000+ hotel rooms and $1.8 billion in economic impact over the last three years, due to the shrinkage of production work here.

In October, the production equipment camera/lighting company ARRI Rental closed its Fort Lauderdale office after 14 years serving the South Florida film and TV industry — and opened a new one in Atlanta. Cineworks Digital Studios, a post-production outfit in Miami that became the first U.S. film laboratory to be certified by Kodak ImageCare in 2009, relocated its Miami office to Louisiana in 2015.

Small businesses are being squeezed, too.

Juan Carlos Alvarez is the owner of Trade Audio, a 27-year-old Miami company that sells, rents and repairs walkie-talkies. Alvarez says business was booming from 1994-2005, when he provided on-set communication gear for the crews of the movies “True Lies,” “Ace Ventura: Pet Detective,” “There’s Something About Mary” and “Any Given Sunday.”

Today, he’s had to get creative in order to keep his doors open, since his business has dropped more than 50%. “If I only relied on film work, I’d be closed right now,” he says. “We’ve had to adopt other strategies outside of movies and become more aggressive in doing repairs for other companies and working with other vendors.”

Gary Ackerman founded his security company G-Force Protective Services and Training Academy in Miami in 2009 and was hired soon after by a small crew shooting a low-budget film in Fort Lauderdale.

“I was told when you do a good job in the movie industry, your name gets passed around and you’ll be the person everyone relies on,” Ackerman says.

It proved to be true. Security gigs on movies and TV shows such as “Rock of Ages,” “Pain and Gain,” “Magic City,” “The Glades” and “Graceland” brought in so much work that in 2013, Ackerman had a staff of 200 full-time security guards billing 4,000-5,000 work hours per week.

Today he’s down to 20 part-time guards. “I’m hard-pressed just to get them 40-hour work weeks.”

Dominoes falling

The erosion of Miami’s film industry carries another troubling side-effect: The irreplaceable loss of crews and talent with deep experience.

Molly Rogers, the Emmy-award winning costume designer who worked on “The Devil Wears Prada,” HBO’s “Sex and the City” and its two spin-off movies and “Ballers,” was relaxing at her apartment on the Venetian Causeway when she got a call from the Atlanta crew of the two “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay” pictures. They needed 1,000 fur coats to dress extras for a big crowd scene and asked if she could fly to New York to buy them.

“I told them there was no point in going to New York and that I could do it from here,” says Rogers, who hopped on U.S. 1 and drove north from Miami to Palm Beach. “I stopped at every vintage and consignment shop that was on my little map I took off the Internet.” The film producers were so happy, they hired her for a nine-week gig to help out with the shoot.

But although she says she longs to be home in Miami, Rogers has been working in Atlanta since August on the FOX TV series “Star” by “Empire” producer Lee Daniels.

“The entertainment industry is all about relationships and connections,” she says. “You get work from recommendations by people you’ve worked with. And you’re starving if you’re trying to stay in South Florida. You have to be like a migrant worker — go where the work is. And that means being away from your family and missing your kid’s school play.”

FLORIDA IS LOSING SOMETHING INCREDIBLE BY KILLING A MAJOR INDUSTRY.

Veteran sound mixer Mark Weber

Chris Ranung, president of the Florida film-technician union IATSE Local 477, says the current number of his members who are Miami Dade County residents is at 198 — down from 245 two years ago — and continuing to fall.

“We have a serious talent drain happening,” he says. “We’re not just losing workers; we’re also losing top talent who can teach and mentor and bring the next generation along, so when people come here to film, we have crews. To work in this industry requires a long apprenticeship, and when we lose the production designers and coordinators, that’s going to hurt our industry for years to come.”

Ranung is also the chair of the Congress of Motion Picture Associations of Florida (COMPASS), which is preparing a bill that would establish a direct investment program for Florida film production that doesn’t rely on tax incentives of any kind.

Miami-Dade Office of Film and Entertainment commissioner Sandy Lighterman is also working on a program, which she hopes to have before the city commission by summer, to attract movie and TV productions to the city.

But even productions in which Miami plays a starring role can’t film here, because financiers won’t sign off on the higher costs..

Take “Deep City,” a new music-heavy dramatic series announced at the NATPE convention in Miami Beach last month. The show, which is being developed by Tandem Productions and sold internationally by StudioCanal, would be created and written by former Miami Herald staff writer Juan Carlos Coto, who currently oversees El Rey Network’s horror-western “From Dusk Till Dawn.” and executive-produced by two Oscar winners, screenwriter Callie Khouri (of the 1991 film “Thelma & Louise”) and music producer/songwriter T Bone Burnett.

Tandem CEO Rola Bauer told the Herald at the time of the announcement that the show, which was inspired by her visits to Miami to attend NATPE, would be filmed on location here. But Lighterman says that probably won’t happen.

“They will shoot some stuff here, because they have to, but it will be second-unit [exteriors and establishing shots],” she says. “The rest is going to be done in Georgia. [The producers] even asked me to introduce them to the Savannah film commissioner, which of course I did because you want to build those relationships. They will do the interiors and some of the exteriors there. They said ‘If you get something, we want to come here, but if you don’t, we can’t make the dollars work, especially when the studios are saying go where the incentives are.’”

Big-budget film producer Randall Emmett (“Silence,” “Lone Survivor”), a Miami native and New World School of the Arts graduate, says what is happening to Florida’s film industry is a “tragedy.”

“I always tell people you can make almost any kind of movie in Florida, because it’s a great location state — it can look like 30 different places,” he says. “But my investors don’t allow us to shoot in non-incentive driven states.

“If you have a $20 million budget and you go to the proper place, your budget becomes $15 million. Then you sell off foreign rights. If you don’t have incentives, then the financiers have to recoup the difference.”

“Vandal” director Jose Daniel “Jaydee” Freixas and cinematographer Caleb Heyman shoot a scene in Little Havana in December 2016.Jayme Gershen

Low-budget productions such as “Moonlight” are still trickling in. Writer-director Jose Daniel Freixas and producer Tony Gonzalez shot “Vandal,” a drama about a Miami graffiti artist, in December and January, using Art Basel events as a backdrop. A lot of the crew members who worked on the film, which was not a union production, have already moved out of Miami but came back for the sake of the movie.

Gonzalez says that despite the limited budget, it was important to shoot “Vandal” in Miami.

“We really wanted to show the city from a side that’s never been shown,” he says. “We have an unwritten rule in this movie that we’ll have no shots of the ocean. And we wanted to capture the true grit and soul of Miami. We wouldn’t have the performances we got if the actors weren’t being exposed to the hodgepodge of personalities here.”

For their follow-up project, Freixas and Gonzalez are developing a drama with Paramount Pictures about the Cuban Mafia, with Benicio Del Toro in talks to star. The budget could be as high as $100 million. They already know they won’t be shooting it in Miami.

Bleeding talent

Mark Weber, 68, has been on film sets since the early 1980s, working his way up from running cables and handling boom mics on “Days of Thunder” and “Cocoon: The Return” to being the sound mixer on the 2005 Wes Craven airplane thriller “Red Eye,” the Jim Carrey-Ewan McGregor 2009 comedy “I Love You Philip Morris,” the 2012 musical “Step Up Revolution” and TV’s “The Vampire Diaries,” which is currently airing its final season.

But after his current gig as sound mixer on “Bloodline” is done, he’s considering relocating from his current home in Palmetto Bay.

“My wife keeps asking me why I don’t retire and find a hobby — something I like doing,” he says. “But I’m already doing that! I’m probably more adaptable than most, because I don’t have to worry about making a lot of money. But my wife is looking at houses in Savannah, because there’s a $2,000 incentive for film crews to move there. Florida is losing something incredible by killing a major industry.”

Gregory Shepherd, the dean of the school of communication at the University of Miami, says he was forced to launch a Semester in Los Angeles program in order to allow film students the opportunity to spend time on film and TV sets, because the opportunities in Miami have dried up.

“I wish we had the opportunity to access those out-of-classroom experiences here locally, but it’s so hard,” he says. “The loss of the industry here means educational opportunities are lost too, becauss students can’t get internships on productions or develop collaborative relationships.

“The state worries all the time about the loss of tech talent to Boston and Silicon Valley. But we don’t seem to worry about losing these amazing writers, producers, and directors. I have students who, if they had a choice, would stay and work here after graduation. Now they have to move elsewhere to practice their craft.”

WE HAVE PEOPLE HERE WHO HAVE WORKED ON MOVIES FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS. BUT ALL THIS KNOW-HOW IS SLOWLY TRICKLING AWAY AND WE’RE GOING TO BE LEFT WITH NOTHING.

Makeup artist Claudia Pascual

Graham Winick, film and event production manager for the City of Miami Beach, is helping Film Florida develop a proposal, called the Education Retention Bill, that would offer a 5-20 percent reimbursement to any film, TV or digital media project in which one of the key primary roles — actor, writer, director, producer — was filled by a graduate of a Florida university.

The modest program would have a cap of $500,000 per project. But Winick, who served as president of Film Florida in 2010 when the state tax incentive program was approved, believes it’s enough to lure smaller projects to the state.

“When they do their balance sheets, most producers ultimately aren’t looking for the best incentive,” he says. “It’s about having something, so they don’t look bad to their investors. We have more film and digital media education programs than any other state. We have two of the top 20-ranked film schools in the country, Florida State University and Ringling College of Art and Design. We collectively invest $500 million a year in Florida Prepaid programs and Bright Futures Scholarships.

“But we’re effectively investing to educate and fine-tune another state’s work force, because when these students graduate, there are no incubator jobs for them to start with, so they move to California or Georgia to start their careers. That makes no economic sense. This is a high-paying, future economy workforce that we should be cultivating and retaining.”

Back in the day

Jennifer Radzikowski, a longtime Miami location scout who served as production manager for “Moonlight,” says she was lucky that when she graduated from UM in the 1990s, the local film industry was thriving. She worked with director Mike Nichols on “The Birdcage,” Sydney Pollack on “Random Hearts” and Bob Rafelson on “Blood and Wine,” among others.

“I had my choice of A-list directors to work with,” she says. “They were coming to Miami and shooting full-length feature films, which is different than the trend today. Everybody I know that’s tried and true and are real artists in the industry have relocated. We’ve lost such a dear industry here.”

Although she keeps a home in Miami, Radzikowski says at least 60 percent of her work in the last three years has been out of town.

And not all of Miami’s film industry workers can move to where the work is. Makeup artist Claudia Pascual, who graduated from music videos and commercials into feature films, has been in the industry for 28 years. She says she is able to travel for work — such as two months in Boston and Detroit working on director Kathryn Bigelow’s still-untitled drama about the 1967 riots, or Hawaii for last year’s comedy “Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates” — because her husband holds down the fort while she’s away.

But she’s unable to relocate permanently because her son is attending college here and her mother and handicapped sister, who live five blocks away, rely on her assistance.

“Every time a crew comes here from New York and L.A., they are surprised by how professional we are,” she says. “We have people here who have worked on movies for more than 30 years. We know how to work with the elements here. We know how to handle humidity. We know which products work here. You can’t used a water-based foundation in Miami. But all this know-how is slowly trickling away and we’re going to be left with nothing.”

Director Michael Bay and actor Mark Wahlberg on the set of “Pain and Gain,” a $26 million production shot in Miami in 2013.Robert Zuckerman

Filmmaker Brett Ratner, a Miami Beach native whose RatPac Entertainment has co-produced movies such as “Sully,” “Suicide Squad” and “The Revenant,” says he might have never pursued a Hollywood career if there hadn’t been film production in town when he was growing up.

“When I was a kid I would skip school and go to the sets of ‘Scarface’ and ‘Miami Vice,’” he says. “Watching them filming made me feel like that was something I could do, because I saw it happening with my own eyes. I probably would have ended up becoming a radiologist like my grandfather instead.

“Florida is one of the greatest states for filming and production, not only because of the scenic nature of the state but because of the quality of below-the-line talent that is very experienced and lives there. Once you take that away, it eliminates the possibility of other young people being influenced and inspired.”

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/biz-monday/article130883349.html#storylink=cpy

[/sm_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]